Artistic interpretation of Dante’s epic

Dante’s The Divine Comedy in Mirko Rački’s Drawings

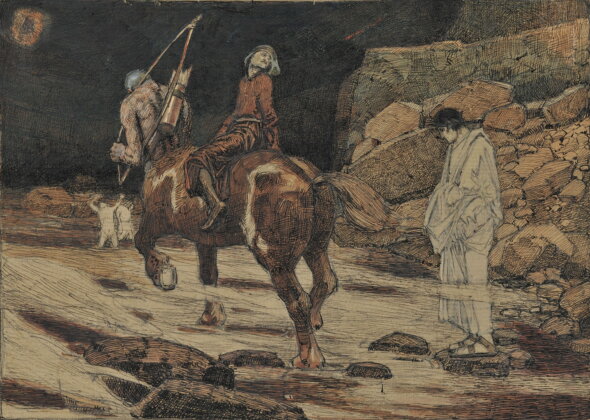

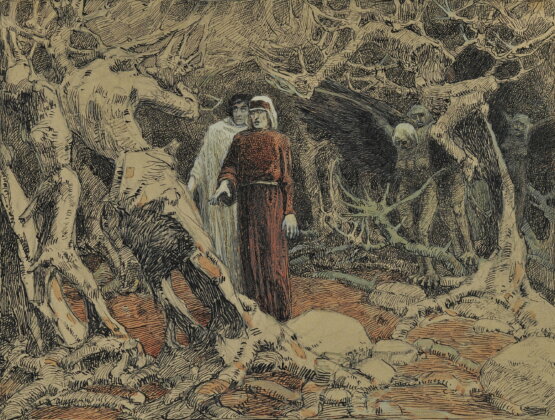

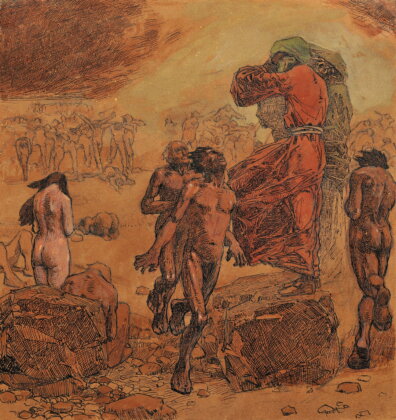

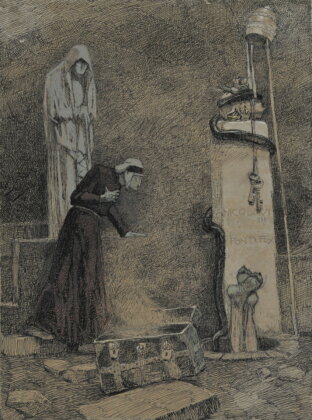

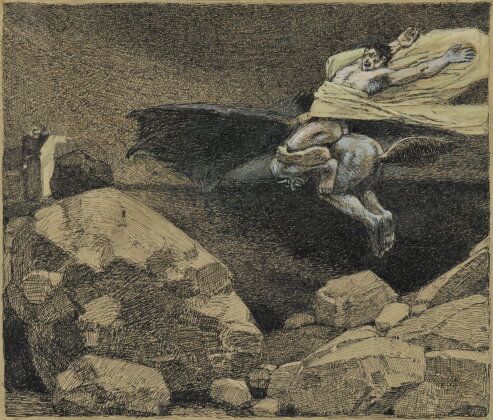

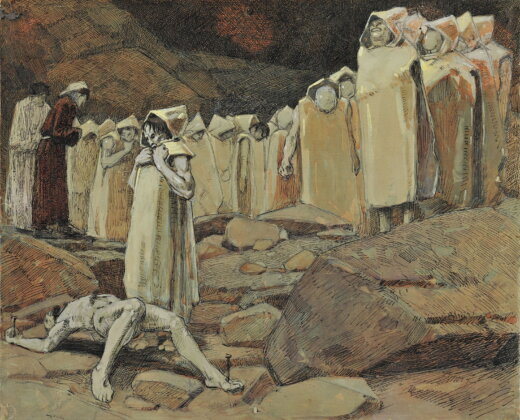

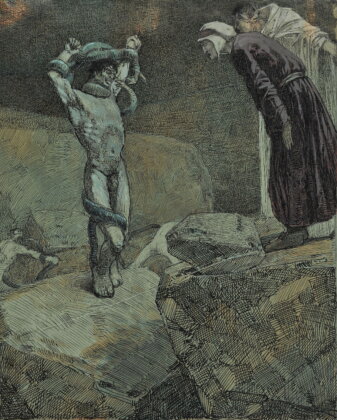

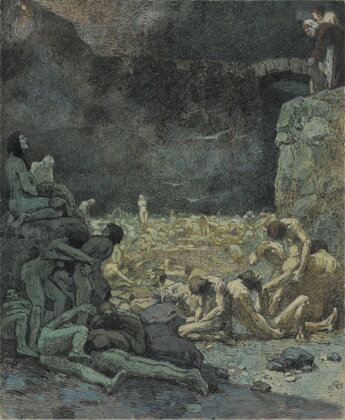

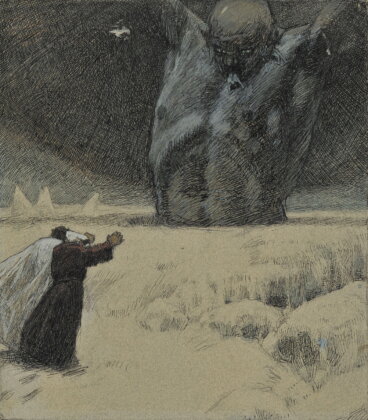

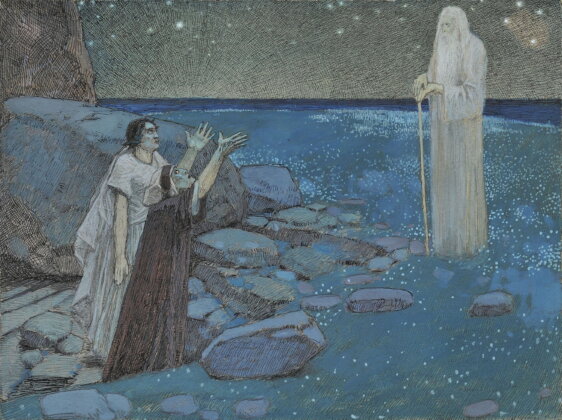

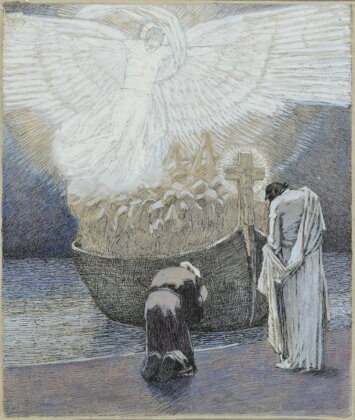

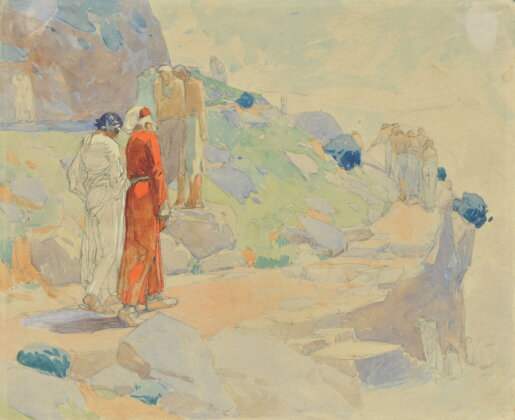

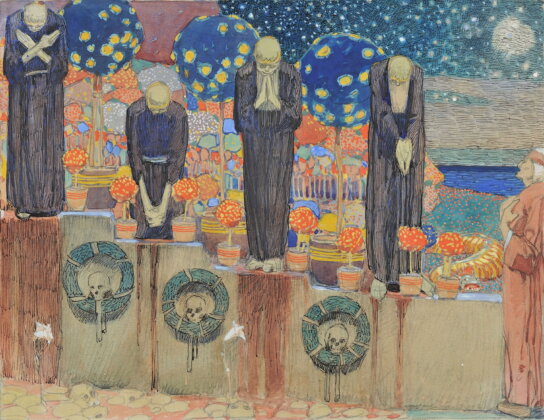

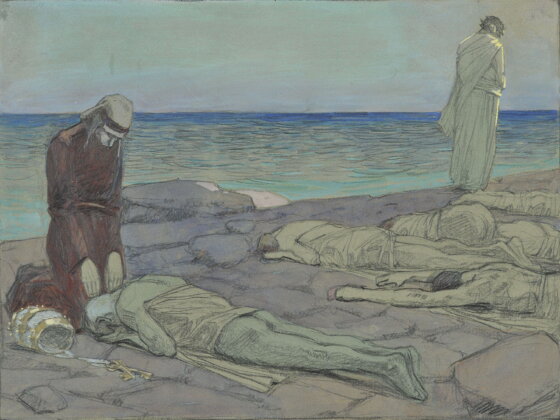

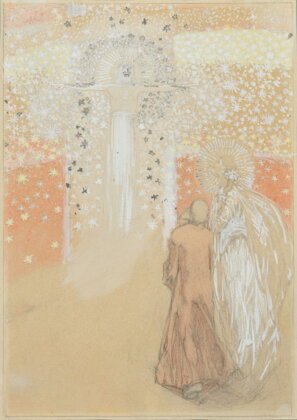

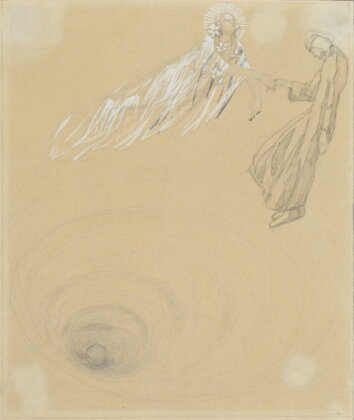

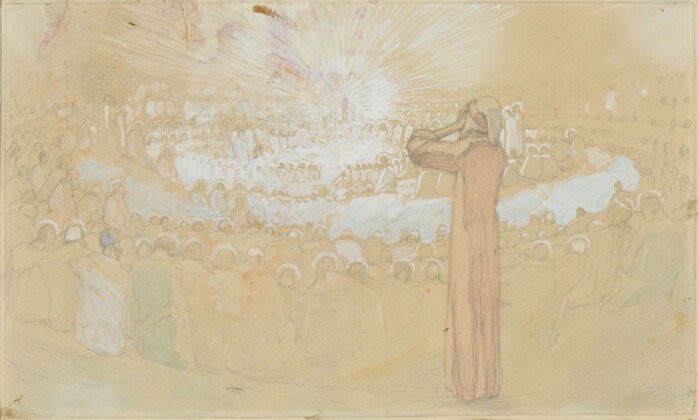

The second series of illustrations for Dante’s The Divine Comedy is one of the most beautiful drawing units, of anthological value in the holdings of the prints and drawings collection of the Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The stylistic and morphological qualities and the homogeneous drawing constituents of Mirko Rački’s impressive illustration work synthesise a broad repertory of a powerful symbolist vault filled with demonological and angelological aspects, allegorical, otherworldly and fantastic narratives which, finally, reveal Rački’s true respect for Dante’s grand epic, as well as a liberated illustrative intention of his brave detachment in the artistic interpretation of Dante’s metaphor. Thirty drawings of the second illustration series were published in the second edition of Kršnjavi’s translation of Inferno in 1919 and thirteen in the third in 1937, whilst the Purgatorio and Paradiso drawings from 1911 were never published. New versions of the 1920s and 1930s illustrations for the representative editions of Purgatorio and Paradiso (1939)[15] were drawn in poorer quality of a schematised linear illustration without a single trace of the dignified Art Nouveau definitions characterised by a dynamic linear combination and colour-related evocativeness. From the point of view of today’s critical reception of modernism, Rački’s Danteological work can be bore broadly conceptualised, beyond formal analyses in the examination of content over visual form, acquiring the essential outlines inside the hypothesis of the European “demon of modernity”.[16] Professional and scholarly criticism after the 1960s[17] theoretically corroborated with clearly defined postulates of modernism and the trends within its time span highly praised these drawings. Examining the entire rich opus in which symbolism of the Danteological cycle and later ideologised monumentalism of heroized folk epic represent two spheres of his work, we should underline the Art Nouveau auratism of his early 20th century drawing concepts. Mirko Rački, often called a ‘Nestor’ of Croatian painting, in his eight decades of creative activity left behind an impressive body of work, first and foremost characterised by symbolic realism[18] anchored in the Art Nouveau ‘interlude’ between academism and historicism, and impressionism and the growing expressionism of the Croatian modern. Rački, educated at the hearts of Art Nouveau in Vienna, Prague and Munich, in the first two decades of the 20th century conceptualised symbolist trends by ingraining his works into the foundations of Croatian, and with his illustrations for The Divine Comedy into the traditions of European modern history as well.

Genesis of drawings for the Croatian editions of Dante’s The Divine Comedy

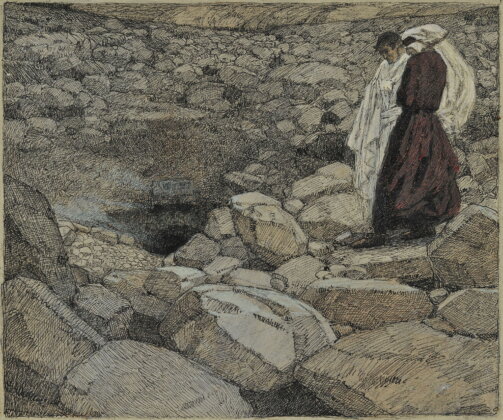

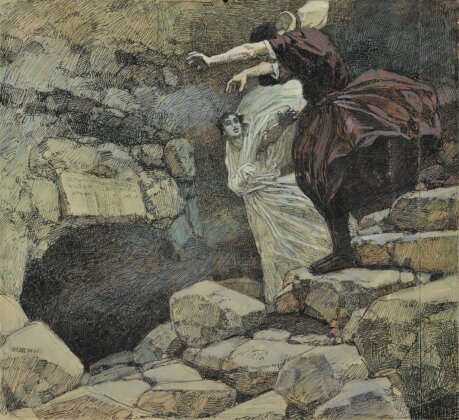

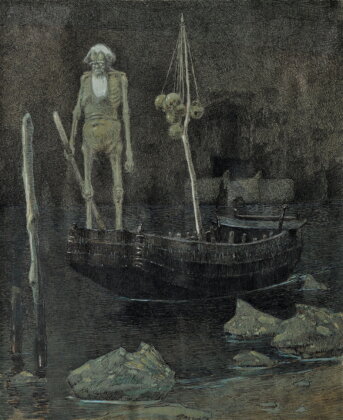

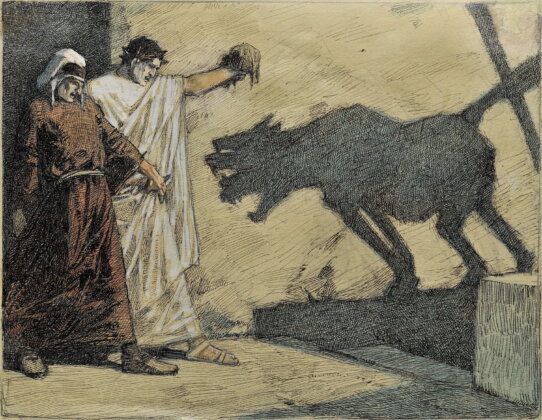

As Izidor Kršnjavi’s protégé, while still a disciple of Vlaho Bukovac in Prague in 1904, Mirko Rački was commissioned by the Art Society to make a series of illustrations for Kršnjavi’s translation of Dante’s epic, a task which he finished in Munich in 1907. This first series of illustrations comprising eighteen drawings, two watercolours and one etching, was displayed at the Meštrović-Rački exhibition in 1910 and sold after the International Exhibition in Rome in 1911. It is kept in the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Uffizi Gallery in Florence.[1] In agreement with the president of the Art Society, Kršnjavi, in 1911 Rački made the second cycle of 53 drawings[2] which was exhibited in 1912 in Amsterdam and at the Art Society’s exhibition in Zagreb in 1913. Today this anthological corpus is part of the holdings of the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The cycle was displayed in entirety in 1979, celebrating the artist’s 100 th birthday, at the exhibition Mirko Rački / Drawings and Prints / From the Holdings of the Department of Prints and Drawings of the Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts.[3] Also, seven sketches for Dante’s The Divine Comedy editions were exhibited: the sketch for Charon (inv. no. 5381/4) and Cerberus (inv. no. 5381/3), three sketches for The Wood of the Self-Murderers (inv. no. 5381/2,6,7), which we dated after 1920, and two sketches from the 1930s, Guido da Montefeltro (inv. no. 5381/5) and Paganello Has Pia Thrown out of a Window (inv. no. 5381/1) for illustrations in the lavish 1937 edition of The Divine Comedy.

Thirty illustrations for the second series of Kršnjavi’s translation of Dante’s Inferno were published in 1919 by the Graphics Institute of Yugoslavia and thirteen were published in the third edition by Typography in 1937. Water-coloured drawings of our series of Purgatorio and Paradiso were unfortunately never published.

Influences of European modernist trends

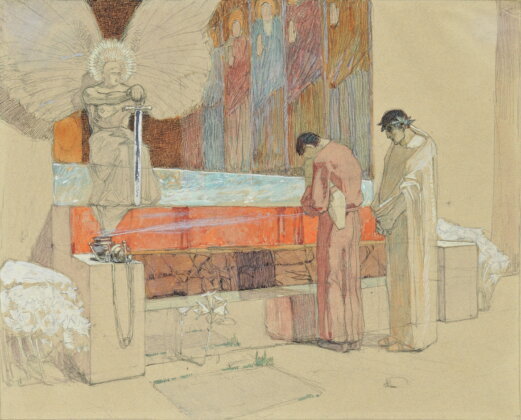

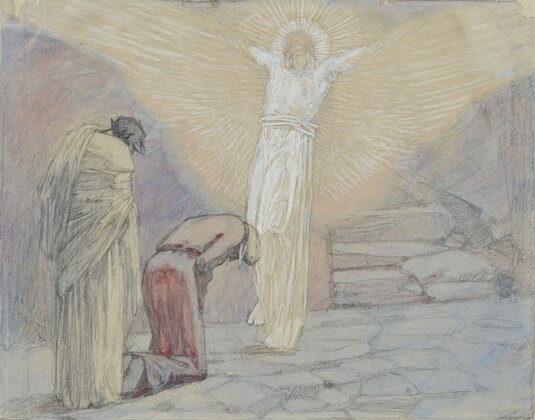

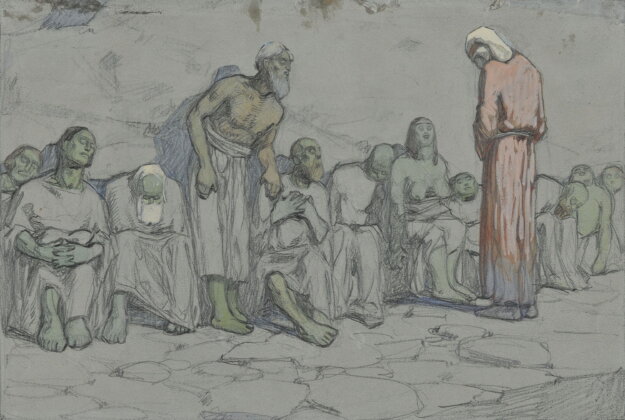

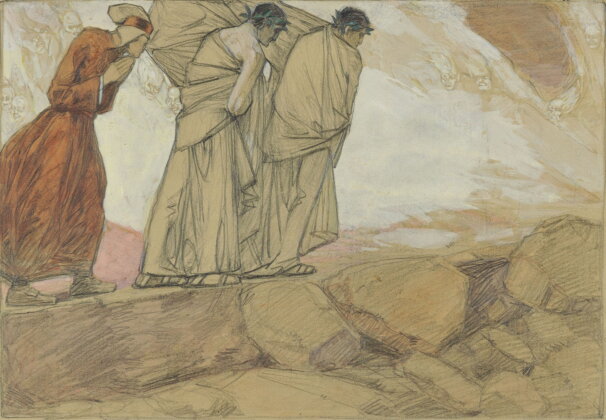

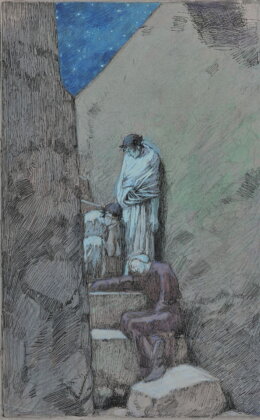

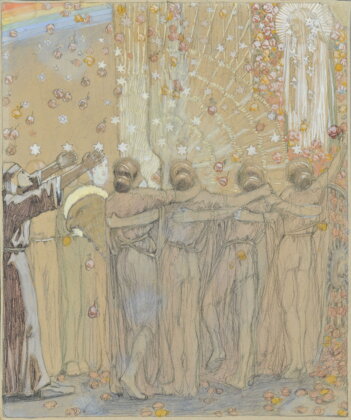

According to Jelena Uskoković (1979: 31, 35, 59-64), the author of Rački’s monograph, the first two series of illustrations for Dante’s The Divine Comedy could be categorised as early modern symbolism, influenced by Art Nouveau tendencies from Vienna and Munich’s Jugendstil decorative style. Judging by the narrative design elements – a freer approach to the visual interpretation of a literary text, the cyclic change of sequences, occasional shifts in proportion and spatial relations and the diabolical repertory – they almost fully comply with Hofstätter’s definition of symbolism.[4] Viennese Art Nouveau influences are more evident in expressive eerie dark scenes of the dense metaphor of hell, and the influences of Munich stand out in flat and aestheticized ethereal concepts of purgatory and paradise. Rački’s artistic disposition took shape until the 1920s in the European centres Vienna, Prague, Munich and Geneva, and his early works reflect symbolist influences (Doré[5], Blake, Jettmar[6], Klinger, Klimt, von Stuck, Hodler, Rops, Bukovac) within the individual idiom characterised by strictness and homogeneity of the drawing composition, a rhythmic exchange of lighter and darker parts, a strong and restless brushstroke and contouring characters in a clear condensation of the entirety.

The themes of Dante’s Comedy preoccupied Mirko Rački at a later stage as well, after returning to his homeland in 1920, but precisely these early symbolically conceptualised drawings and paintings attribute Mirko Rački as the most significant representative of Croatian and even European modern art of the early 20 th century.

Dante’s verses in evocative drawings of the second series of illustrations for The Divine Comedy

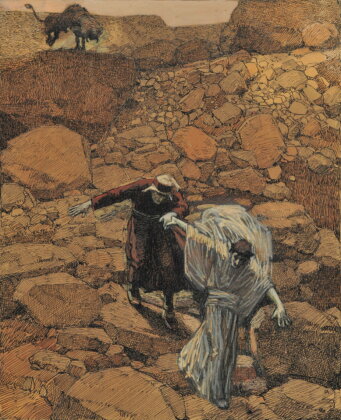

Drawings inspired by Dante’s The Divine Comedy reflect Rački’s excellent insight and appreciation of this anthological endeavour of the human spirit,[7] however a freer illustrational approach in composing the entirety points to the imaginative strength of the artist’s drawing skills in reconciling the boundaries between the hypotheses of the literary paradigm and interpretative freedom. As early as in his first series of drawings for The Divine Comedy, Rački in a certain manner detached himself from the literal transferral of verses into drawings, amply present in the correspondence between him and the Dante scholar and translator Kršnjavi.[8] However, as much as Dante’s magnificent cantos teem with picturesque descriptions, in order to comprehend the drawings in their entirety one should not lose sight of the impact of Kršnjavi’s historical, philosophical and theological interpretations and allegorical explanations of the epic. Finally, the evocative drawings, based on a literary sample, reveal the powerful fantasy of the illustrator who daringly composes his concepts to provide his drawings with a quite personal idiomatic intonation.[9] It is visible in the choice of the most impressive narrative moments of the epic, which he supplemented with symbolically charged fantastic and surreal elements.

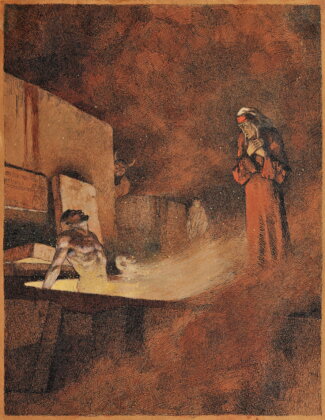

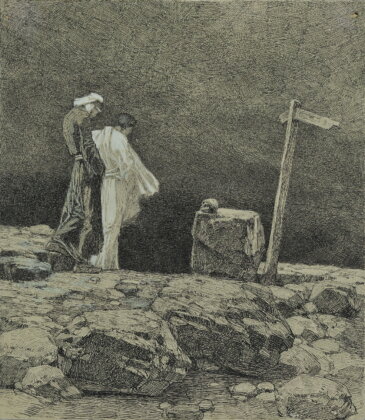

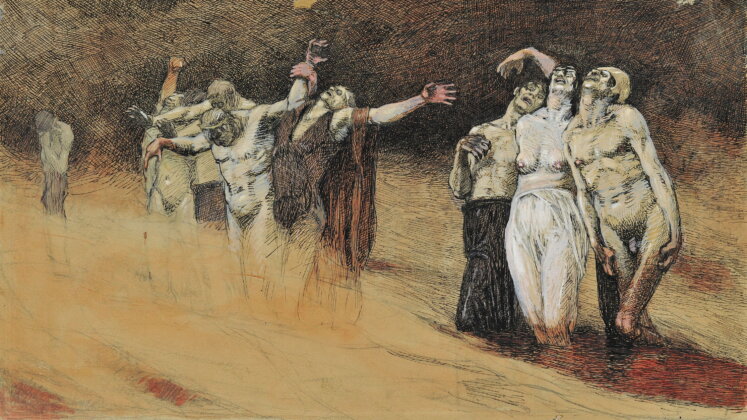

Critic Vladimir Lunaček (1919: 2) in his review “Račkijeve risarije k Danteovu Paklu” published in Obzor in 1919 correctly determined Rački’s illustrations as “pen-drawings”.[10] The original ink drawings from our holdings possess an accentuated and vibrant quilled basis of a dense line structure characterised by short energetic crosshatch strokes. They were deliberately drawn on dark toned paper which highlights the ominous and dark infernal atmosphere of the composition. The hellish scene drama is underlined by watercolour and gouache which in the scenes of horror, suffering and hopelessness stress the dichotomy between light and darkness. With a subdued colour palette Rački evokes a concealed and eerie atmosphere of hell’s antechamber and the intense red, orange and brown hues underline the atrocity of the horrors of deep hell. A methodological twist is seen in the scenes of purgatory and paradise, dominated by pastel toned watercolours and gouaches and gentle brushstrokes against a graphite background. This considered approach of morphological differentiation between the drawings of hell and watercolours of purgatory and paradise is corroborated by Rački himself: “… Hell is more a thing of drawing. I pictured it to myself as black and white, that is why it has little colour, except in case of fire, then the light comes from flames. Since Purgatory is on a hilltop, it is exposed to daylight. Those few things for Paradise – that is scholastics, I was not attracted to that.” (quoted in: J. Uskoković, 1979: 30)

Summarising the literary aspects of Dante’s epic according to the interpretations of Mate Zorić and Frano Čale (1976: 38), we should stress the succinct atmosphere of every canto according to which Inferno is the richest and the most dramatic content-wise,[11] full of ominous atmospheres, horrific scenes, examples of hate and intense memories of sin, whirlwinds of mundane passions and unclad perversions. The poet’s moments of doubt and invectives and the fantastic descriptions of terrible ordeals that befell the main protagonists, the sinners and their tormentors – devils and monsters, residents of rocky, swamp, frozen or incandescent landscapes – were entirely portrayed by Rački in his impressive and quite personal reconstruction of hell. According to Čale – Zorić (1976: 39), Dante’s Purgatorio is dominated by an atmosphere of elegiac lyricism and mild serenity under the bright blue sky. The emotional atmosphere is filled with notes of remorse, forgiveness, hope and longing for the promised paradisiac bliss; souls of similar physical appearances gather in serene groups, kind conversations take place, chorus singing is heard and light tones prevail – the crepuscular feeling of the evening and the pastel colours of the dawn. Unlike the tangible and atrocious drama of Inferno, Paradiso is content-wise the most abstract canto of the trilogy. Souls in paradise have reached perfection; elevated above earthly interests, they enjoy contemplation an atmosphere of love, justice and mercy, and their appearance has been nullified and replaced with different manifestations of emanating light (F. Čale; M. Zorić, 1976: 39). Leaving the paper surface intact, Rački simulates the ethereal light of heaven’s infinity – applying this method to most of the drawings in Paradiso, which consequently often appear as unfinished, i.e. as sketches.

A selection of reviews by Rački’s contemporaries

Critical reviews written by Rački’s contemporaries of the Danteological cycle praise the today capital works of Croatian modernism – oils on canvas City of Dis (1906), Crossing Acheron (1907), Francesca da Rimini (1908-1909), In the Valley of the Kings (1913), Crossing Styx (1914) and Rose of Paradise (1914), as well as drawings, watercolours and etchings of the same theme.

Among the favourable reviews of the illustrations of Dante’s Comedy was penned by Nello Tarchiani, the managing director of the Uffizi Gallery from Florence, who published a text in 1912 in the Marzocco art magazine about the first series[12] of illustrations with a telling title “Un interpretazione selvagia della Commedia d’Dante” (“A Savage Interpretation of Dante’s Comedy”, quoted according to A. Wenzelides, 1912: 572), underlining the strength of Rački’s drawings which possess “something wild” for which reason he calls them phantasmagorias stemming from his independence and freedom as he “rejoices and enjoys the untruth” of the interpretations of Dante’s epic, concluding that he finds “the finest those drawings starting from Dante’s motif and then freely navigating the infinite fields of imagination.”

According to Jelena Uskoković’s research published in the Rački monograph, the first series of illustrations (1904-1907) was displayed at the International Exhibition in Rome in 1911, was highly praised by both art professionals and audience and subsequently acquired by the Italian government from the Art Society for Gabinetto Disegni e stampe degli Ufizzi.[13] Uskoković (1979: 140, 144, 145, 147, 153, 164, 165) in the monograph publishes photographs of a few first series drawings from the Uffizi collection, illustrating almost identical composition and symbolical narrative and motif concepts repeated by Rački in the second cycle in 1911. It was Lunaček back in 1910, writing about the first series of Rački’s drawings for the Croatian edition of Dante’s Inferno, who already stressed “cynical bits, witty and almost humorous, like, for instance, that road sign in front of the gates of hell…” (V. Lunaček, 1910: 391), and which were kept in the second series of illustrations as Rački’s idiosyncratic iconographic topoi.[14] Although the narrative characteristics of the epic in hell configuration composition concepts and character positioning were respected, it was undoubtedly these inventive motifs complementing the underworld, i.e. their sarcastic repository, that bore the powerful symbolist charge in our series of drawings. Artur Schneider (1912: 7) in his review of Tarchiani’s portrayal of “a savage interpretation of Dante’s Comedy” also points out that “Rački’s imagination in its courage often exceeds even the poet’s imagination.” Andrija Milčinović (1912: 494) also claims that “Rački in his Dante plots is not an illustrator in the ordinary sense, as our and foreign critics noticed (during the recent exhibition in Rome), but rather only draws inspiration from Dante’s text and surrenders to his imagination mostly to guide him in conceptualising and executing an image.”

Only a few reference articles were written about the second illustration series evidencing the critics’ approval of the imaginative power of Rački’s illustrator propensity in reconciling the boundaries between the literary model and interpretative freedom, underlining his imagination and philosophy, as well as virtuosity of composition. The most comprehensive formal analysis and an interesting interpretation “which is quite solitary in the total thus far found critical writings about Rački” (J. Uskoković, 1979: 34) of the second series was expounded by Zdenko Vernić in 1919 in the text “Rački’s Illustrationen zu Dantes Hölle” (“Rački’s Illustrations of Dante’s Inferno) published in Agramer Tagblatt. Zdenko Vernić highlighted the compositional concepts for the “thirty pictures” in colour in which, instead of an expressive colour scheme, the entire procedure is oriented to the light and darkness contrast and the linear domination, and “the grim tone of the underworld pervades every image” (Z. Vernić, 1919: 1).

The versatile intellectual and leading ideologist of Croatian modernism, Milutin Nehajev (1923: 6) in his portrayal of Rački’s exhibition at the Ullrich Salon confirms that Rački possesses “a strong linear perspicacious talent – and the Charons and Ugolinos are only a nice embodiment of an immense dark, philosophically synthesising fantasy.” Kršnjavi (1924: 10) in an essay under the title Mirko Račkis Purgatorio from 1924 in Der Morgen praises Danteological “adaptations” and Mirko Rački’s “closeness” to Dante which “develops the poet’s thoughts and feelings that the poet only evokes, but never enacts.” As Rački’s long-time friend and associate, Kršnjavi had the best insight into the illustrator’s methodology. In the same article he claims Rački used to make a several “same variations” on a theme and within these variations on a particular theme “each variety in itself was a complete work of art, which made it hard to judge which is better.” From Kršnjavi’s legacy, Fine Arts Archive only has a few photographs of different versions of a particular motif, testifying to Kršnjavi’s claims.

The art-criticism point of view of his contemporaries (Kršnjavi, Lunaček, Begović, Marjanović, Nehajev, Križanić, Batušić, Stele, Tomljanović, Šrepel…) in the attempts to valorise Mirko Rački’s Danteological work after the 1960s are further developed and reinterpreted by reviews and analyses of art history theoreticians and critics Željka Čorak, Vladimir Maleković, Božidar Gagro, Tonko Maroević, Grgo Gamulin, Zdenko Rus and others.

Conclusion

The second series of illustrations for Dante’s The Divine Comedy is one of the most beautiful drawing units, of anthological value in the holdings of the prints and drawings collection of the Department of Prints and Drawings, Croatian Academy of Sciences and Arts. The stylistic and morphological qualities and the homogeneous drawing constituents of Mirko Rački’s impressive illustration work synthesise a broad repertory of a powerful symbolist vault filled with demonological and angelological aspects, allegorical, otherworldly and fantastic narratives which, finally, reveal Rački’s true respect for Dante’s grand epic, as well as a liberated illustrative intention of his brave detachment in the artistic interpretation of Dante’s metaphor. Thirty drawings of the second illustration series were published in the second edition of Kršnjavi’s translation of Inferno in 1919 and thirteen in the third in 1937, whilst the Purgatorio and Paradiso drawings from 1911 were never published. New versions of the 1920s and 1930s illustrations for the representative editions of Purgatorio and Paradiso (1939)[15] were drawn in poorer quality of a schematised linear illustration without a single trace of the dignified Art Nouveau definitions characterised by a dynamic linear combination and colour-related evocativeness. From the point of view of today’s critical reception of modernism, Rački’s Danteological work can be bore broadly conceptualised, beyond formal analyses in the examination of content over visual form, acquiring the essential outlines inside the hypothesis of the European “demon of modernity”.[16] Professional and scholarly criticism after the 1960s[17] theoretically corroborated with clearly defined postulates of modernism and the trends within its time span highly praised these drawings. Examining the entire rich opus in which symbolism of the Danteological cycle and later ideologised monumentalism of heroized folk epic represent two spheres of his work, we should underline the Art Nouveau auratism of his early 20 th century drawing concepts. Mirko Rački, often called a ‘Nestor’ of Croatian painting, in his eight decades of creative activity left behind an impressive body of work, first and foremost characterised by symbolic realism[18] anchored in the Art Nouveau ‘interlude’ between academism and historicism, and impressionism and the growing expressionism of the Croatian modern. Rački, educated at the hearts of Art Nouveau in Vienna, Prague and Munich, in the first two decades of the 20 th century conceptualised symbolist trends by ingraining his works into the foundations of Croatian, and with his illustrations for The Divine Comedy into the traditions of European modern history as well.

Ružica Pepelko

***

[1] The Society allowed the sale of the first series to Uffizi, and Rački undertook the task of remaking the same inventions.

[2] Most drawings in Inferno are almost identical to the first series, while the drawings in Purgatorio and Paradiso are completely new.

[3] The catalogue introduction was written by the former manager of the Department of Prints and Drawings Renata Gotthardi-Škiljan, and the preface and catalogue were compiled by curator Marija Grbić.

[4] In his book Symbolismus und die Kunst der Jahrhundertwende (Verlag M. DuMont Schauberg, Köln, 1973).

[5] Uskoković in his monograph Rački (1979) points out only two scenes, Farinata and Cavalcanti and Caiaphas and Hypocrites, which remind of the then most famous The Divine Comedy illustrations, made by Gustave Doré.

[6] Ibid.: “Hell is closer to Jettmar’s academic-realist symbolism.”

[7] Rački read The Divine Comedy in French and German and started learning Italian to read the original (J. Uskoković, 1979: 30). Otherwise he was a polyglot and by his very old age he became fluent in approximately ten world languages.

[8] In April 1904 Kršnjavi offered Rački to illustrate Dante for his translation from the Italian, and their letters are kept in the Croatian State Archives, abounding in data about the sketches for illustrations and paintings. Between 1908 and 1912 there were no letters between the two of them.

[9] In the text “Rački ispravlja. Netočni podaci u Jugoslavenskoj enciklopediji” (B. Đorđević (wrote), Oko, Zagreb, 1979, year 6, no. 183, p. 6) Rački steadfastly claims that the quill drawings for The Divine Comedy were not carried out according to Kršnjavi’s instructions, but rather according to ‘his own creation’. He would also be angry at his contemporaries for his entire creative life span for “trying to make him an illustrator of Dante”.

[10] These thirty black and white illustrations of Inferno published by the Graphics Institute of Yugoslavia in 1919 was analysed by critics of the time through the eyes of the print’s overaccentuated chiaroscuro.

[11] Because of its vibrant content, Dante’s Inferno has always posed the greatest challenge to translators, interpreters and illustrators.

[12] Exhibited in the pavilion of the Kingdom of Serbia at the International Exhibition in Rome in 1911.

[13] The cycle bears the inventory numbers 20968-20988 (Lj. Leontić, 1955:6)

[14] As far as differences between illustrations and Dante’s verses are concerned, Lunaček in the same text lucidly concludes that “it is the opinion that distinguishes them” because “they are more than four centuries apart” (!).

[15] Alighieri, Dante: Božanstvena komedija. Translated and interpreted by Izidor Kršnjavi. 3 rd edition, Naklada Tipografije, Zagreb, 1937 – 1939, 3 vol.: Pakao (with 32 pictures by Mirko Rački, 1937); Čistilište (with 17 pictures by Mirko Rački, 1939); Raj (with 17 pictures by Mirko Rački, 1939).

[16] Giandomenico Romanelli’s expression that brilliantly covers the symbolist motifs of modernist trends in the first decades of the 20 th century (see exhibition catalogue Demon of Modernity, Modern Gallery, Zagreb, 2015).

[17] Revitalised by the exhibition Medulić Association of Croatian Artists in 1962.

[18] Rački clearly defined his creative style as “realism-based symbolism” (quoted in: J. Uskoković, 1979: 29).